T’AI CHI CH’UAN in ENGLISH

T’AI CHI CH’UAN – Robin John Simmons

INDIVIDUAL AND GROUP CLASSES ARE AVAILABLE – PLEASE CONTACT ROBIN FOR DETAILS

These ancient movements are performed with utter slowness and attention. Practiced in China for hundreds of years they are very relevant for today’s turbulent world.

The movements are attractive to watch yet they are not really intended for demonstration. Indeed, they form a meditative movement exercise for the essential benefit of the practiser. Improved health, the fluidity of action, calmness and tranquillity, balance and strength come from practicing T’ai Chi.

Once learned it can be done anywhere where there are a few yards of space, just for two ten-minute periods each day

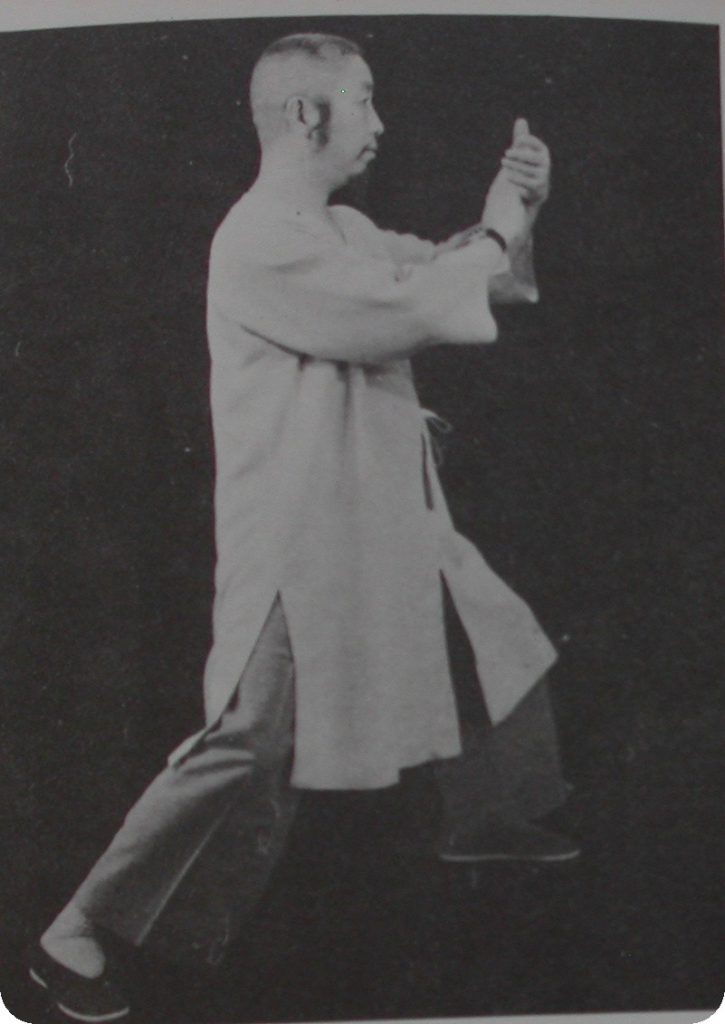

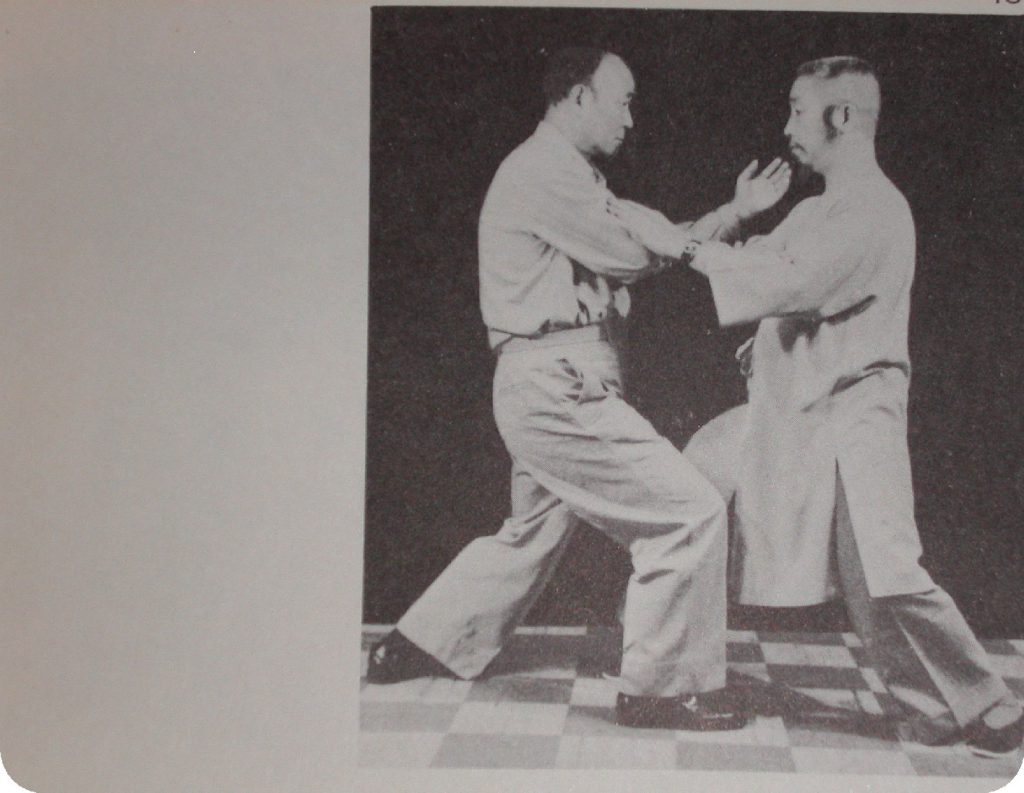

To begin learning T’ai Chi, the Short Form of 65 movements is the best and simplest way. This “form”, devised by Cheng Man-Ching from the Long Form of 150 movements, is both economical and perfect in itself. It is now well established and practised world-wide. It embodies the essence of T’ai Chi in the unity of the flowing action and the development of ‘centredness’. Later, for those who have time for it, the Long Form and also forms working with a partner can be learned. Youtube video

Robin John Simmons has been working with T’ai Chi since 1969. He has had a number of teachers mainly stemming from the Cheng Man-Ching/T.T. Liang line including Dr. Chi Chiang Tao. He has taught people of all ages and backgrounds, including well-known TV and film stars, he has run large group classes and also individual sessions.

Anyone can learn to tune in to the quietness and inner calm the practice of T’ai Chi brings. At present Robin is only giving individual sessions in Switzerland.

T’ai Chi Ch’uan: An Introduction

T’ai Chi Ch’uan might be translated as “supreme ultimate fist”. However, the word “fist” gives the wrong impression. “Shadowboxing” maybe better. In T’ai Chi the movements are fundamentally meditational (not aggressive at all) – both by being performed very slowly and also because continuous mindfulness and awareness of the whole body in action is essential. If you slowly form a fist you are enclosing a small space within your hand. In this way, you create small darkness (yin), but the way you do it in T’ai Chi means you leave a small hole through your fist, and you can see through this small hole to the daylight at the other end of the hole (yang). T’ai Chi is the continuous interplay of “yin” and “yang” forces. So the translation may be “supreme ultimate interplay of cosmic forces”.

T’ai chi is a very ancient movement practice going back hundreds of years – in fact, the origins of T’ai Chi are unknown. The versions handed down today are, according to legend, developed from the ‘creator’ Chang Sang Feng in the 12th century, but it is clear that the real origins go back way before his time. I started T’ai Chi in 1969 and have had several teachers including John Yalenezian, Seeow Poon Shing, and especially Dr. Chi Chiang Tao among others.

The lessons in T’ai Chi

My T’ai Chi lessons always start with a period of stillness and with preliminary practices that are designed to bring about a state of active watchfulness. Giving attention to prevent our misdirected psycho-physical habitual actions is inherently promoted in T’ai Chi as the movements are performed with immense care, so there is plenty of time to observe one’s use, or misuse, and prevent unwanted actions. Actually, unconsidered actions are virtually impossible in practicing T’ai Chi, for as soon as you lose conscious connection to the actions you are performing, you find you make a mistake which brings you up short.

Conscious directions and mind-body unity

In T’ai Chi the directions you must consider in performing the actions require that you make movements of the whole body, arms, and feet, related to the 8 directions of the compass. Sequentiality must also be observed as the ‘waist’ in T’ai Chi is supposed to lead every action – like a ‘banner’ as the T’ai Chi Classics state. Also, the arms must always ‘follow’ the torso body actions. The continuous maintenance of a central awareness of the whole body moving in a coordinated unity in an upright, yet ‘relaxed’ manner is of primary importance in T’ai Chi.

“Relaxed” does not mean collapsed

Prior to starting the T’ai Chi sequence it is recommended to adopt a certain upright and yet also “relaxed” body attitude. In T’ai Chi, teachers speak about having the body suspended from underneath the head as if the body were hanging from there like a piece of cloth held up. Trying hard to be upright or having some wrong and confused idea of an imagined string attached to the top of one’s head pulling one up are images implying unnecessary effort which is quite the opposite of the T’ai Chi philosophy. Suspension from under the head with a spine that is tending to lengthen is the way to think about uprightness.

In T’ai Chi you are required to take time to be aware of the whole body in action as one unit. If you focus too strongly on a part like the arms and hand positioning you then might forget your feet and soon find you cannot continue the sequence without returning to where you “lost” them.

Use of the eyes

In T’ai Chi, before starting to move, as well as being aware of the whole body as one unit, it is important to pay attention to where your vision is directed. You should not stare out in front of you but allow your gaze to slightly dip to an area 3-4 meters away on the ground. The combination of this directed vision plus the awareness of the body being suspended from under the head helps to assist the T’ai Chi practicer to free their neck muscles and remain upright but easy.

The indirect approach

Having started to learn the T’ai Chi sequence another principle soon emerges, that of the ‘indirect action’. In T’ai Chi many of the moves are built up by a series of steps that involve sometimes surprising twists and turns. For example, the action or ‘posture’ called Single Whip involves actions that start with the practicer facing due East, and conclude with the practicer facing due West. But to go from East to West the move is not done directly. There are 6 parts to the move. First, you move your weight back away from East; then you swivel around leftwards to face Northwest, after that, you again reverse your weight to the other foot and turn to face Northeast; after that, you twist to face Northwest once more. And finally, you step West, the fifth moment, and then finish by turning your body to face directly West. Altogether this is a very indirect action.

Psycho-physical unity

At the start of performing the T’ai Chi sequence, T’ai Chi practicers are required to be continuously aware of the centre of gravity of the body during practice. This is called being mindful of the “tan t’ien” which is said to be located 2 and a half finger widths below the navel and 7 parts into the body if you divide the body at that point from front to back into 10 parts. In other words, its location is a guess. However, being aware of it even approximately helps to promote the overall awareness of the body as a single unity.

The use of the back, one-foot balance and the knees

If one takes an interest in one’s back while performing T’ai Chi you get new insights into T’ai Chi actions. For example, if you are turning to the right in a T’ai Chi move, you might normally consider turning the front of your body rightwards. However, it is also possible to turn to the right by considering moving the right side of your back backward relative to the left side. This reversed way of thinking to make the move keeps the attention in your back. From this perspective, you once again get a greater awareness of the whole body in action and also a greater awareness of what is happening generally.

In addition, it is often necessary in T’ai Chi to balance well on one foot only. (It has been shown that older people who practice T’ai Chi have half the number of falls than the average). In some T’ai Chi moves it is even necessary to rotate whilst standing only on one foot.

It is also important to give conscious orders related to the action of the knees when moving. By doing this you actively prevent the inward misalignment of the knee joint as you move. In fact, the architecture of the knee joint shows that it is designed to move most freely when the knee is directed out over the toes when flexing – i.e. forward from the hips and with each knee directed somewhat away from the other without that being exaggerated.

Meditation in action, the Yin-Yang balance

In T’ai Chi you are not merely learning a sequence of physical actions. It is essential in T’ai Chi to be psycho-physically aware, to continuously appreciate the whole organism as one unit, to retain the central consciousness of the tan t’ien and to move so slowly that any faulty habit patterns are avoided. But this is not so difficult because the actions of T’ai Chi invite such awareness. The harmonizing effect of the T’ai Chi actions assists in creating a unique alert-yet-meditative quality. So when the left-hand rises the right-hand falls, when the right-hand goes forward the left comes near. Yet, as one of my T’ai Chi teachers, Dr. Chi Chiang Tao said: ‘In T’ai Chi no arm move’. So arm actions are never allowed to dominate but must always follow the whole torso in relation either to weight shift or to body rotation, or both at once.